Insights

Exploring the science, habits, and tools that keep your body and mind balanced.

New

Article

February 13, 2026

time

-min

read

Can vagus nerve stimulation improve sleep?

Research suggests that if your sleep troubles are linked to stress and nervous system imbalance then non-invasive VNS may help. Here’s what the science says.

If you’ve been searching for new ways to get better slumber, you may have heard of vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) and, because you’ve tried a lot of things in vain, dismissed it.

But non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation (nVNS) is proving helpful for certain types of sleep disturbance. It’s not a universal cure, though. Details matter.

Here’s what the science says.

Why the vagus nerve affects sleep

The vagus nerve is the main arm of your parasympathetic nervous system — the system responsible for rest, recovery, and downregulation. It helps you shift out of fight-or-flight, slows your heart rate, reduces alertness and mental overactivity, and stabilizes breathing — all things you need to get good sleep.

If your nervous system stays subtly activated at night, if you go to bed in even a low-grade fight-or-flight state, you may feel that familiar tired-but-wired feeling.

One of the vagus nerve’s primary functions is to keep you coming back to rest-and-digest all through the day, especially before bed.

By stimulating the vagus nerve, you can enhance your body’s natural ability to find rest.

While vagus nerve stimulation has been studied for decades, the focus for a long time was on implanted stimulators. More recently, non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation (nVNS) — stimulation that happens through the skin — is growing in popularity as a promising tool to improve sleep quality.

Let’s explore what research shows about nVNS for sleep.

taVNS for post-stroke insomnia

One published case study using transcutaneous auricular VNS (taVNS) treated a patient with post-stroke insomnia.

After two weeks of receiving stimulation twice a day, not only did the patient’s sleep improve significantly but the patient was still getting better sleep at their three-month follow-up.

Brain imaging (fMRI) showed decreased activity in the default mode network (DMN) — a brain network often hyperactive in insomnia and rumination.

While this was only a single case, it supports the idea that vagus nerve stimulation may calm overactive brain networks linked to poor sleep.

Migraine-related sleep disturbance

People with migraines report more trouble sleeping than others.

A prospective observational study found that nVNS helped:

- Prevent migraines

- Treat acute attacks

- Improve migraine-associated sleep disturbance

This suggests vagus nerve stimulation may be particularly helpful when sleep issues are tied to nervous system dysregulation.

Ear stimulation and insomnia

Cranial electrotherapy stimulation (CES) — low-intensity electrical stimulation applied to the earlobes — is FDA-approved for insomnia, anxiety, and depression.

Although the earlobe has limited vagal innervation, brain scans show CES produces activation patterns similar to vagus nerve stimulation. The concha, cymba concha, and tragus are innervated by sensory branches of the vagus nerve.

These sensory nerve fibers carry the electrical signals of the stimulation into the brain, particularly the nucleus ambiguus, dorsal motor nucleus, hypothalamus, amygdala, and cortex. The hypothalamus controls your shifting between sleep and wakefulness.

The brain may be more receptive during sleep

Animal research shows that the brain’s response to vagus nerve stimulation changes across sleep stages.

Vagal-evoked brain responses are largest during non-REM sleep, suggesting the brain may be especially receptive to vagal input during deeper sleep phases.

We also know that vagal regulation differs across sleep states in newborns, highlighting the vagus nerve’s natural role in sleep architecture.

Are there risks?

Non-invasive VNS is generally considered safe.

However, implanted VNS devices (used for epilepsy and depression) have been associated with sleep-disordered breathing, increased obstructive apnea, snoring, and rare reports of insomnia.

These effects likely relate to stimulation intensity and influence on upper airway muscles.

Importantly, these findings do not automatically apply to modern non-invasive devices like your yōjō — but they do show that stimulation parameters matter.

So, can vagus nerve help me sleep?

Sleep isn’t just about melatonin levels. It’s about nervous system regulation.

Because the vagus nerve influences heart rate, inflammation, breathing, and brain network activity, stimulating it may help the body shift into a recovery state more effectively, beckoning sleep.

For people whose sleepless nights feel like a stress-response problem, vagal modulation could represent an important emerging option.

Article

February 6, 2026

time

-min

read

Do vagus nerve stimulators work for anxiety?

For those living with anxiety rooted in the constant stress of everyday modern life, here’s how vagus nerve stimulation can get you feeling more grounded more of the time.

If you’re curious about vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) for anxiety, chances are there’s some hesitation on your part. So much about VNS is new, unclear, and unfamiliar. It’s sort of stressful.

This article is here to slow things down.

To begin with, yes, VNS works for anxiety. And there is loads of evidence to back us up here, but that’s not enough is it?

“Does this work?” is quite abstract.

Let’s look at the real reasons others hesitate when it comes to VNS for anxiety, reasons you might share with them. And let’s explore the relevant science.

Is this safe?

For many people, the first thing that comes to mind with vagus nerve stimulation is surgery.

That’s understandable. Invasive VNS has been used for years as an implanted treatment for drug-resistant epilepsy and depression. Hearing that can trigger fear around medical procedures, side effects, and long-term changes.

What often gets missed is that non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation (nVNS) also exists — yōjō’s VNS device is a non-invasive, ear-based stimulator.

Non-invasive VNS works through gentle stimulation through the skin. It does not involve surgery. Several studies show that these types of stimulators are safe, and come with very few side effects.

For people already living with anxiety, simply knowing that stimulation can be external, adjustable, and non-surgical removes a major barrier.

I don’t really understand what it does

“Stimulating a nerve” can sound vague or intimidating.

Without a clear mental model, it’s easy for VNS to feel abstract or even questionable.

Here’s the simple version:

- The vagus nerve is a major communication pathway between the body and the brain.

- It plays a key role in the parasympathetic nervous system, which supports calm, safety, and recovery.

- Anxiety is strongly linked to overactivity in the body’s fight-or-flight response.

- A vagus nerve stimulator sends gentle electrical current along the vagus nerve, activating it.

- These bottom up signals travel from the body to the brain, helping shift the nervous system out of constant alert — supporting the body’s ability to regulate itself.

Read more about the vagus nerve and what it does.

Doing this regularly helps improve vagal tone, which improves the vagus nerve’s ability to function properly.

I’ve tried so many things already

Supplements, meditation, apps, therapy. The more of these we try that don’t land, the less hope we have of finding anything that will.

Burn me once…right?

The thing is, VNS research seldom starts with anxiety as the main target. Anxiety is always a secondary outcome in studies on depression or headaches. But it’s almost always recognised as an improvement.

For example:

- In a clinical trial using non-invasive VNS for depression, anxiety scores dropped significantly alongside mood improvements.

- Patients treated with VNS for certain pain and headache conditions also showed meaningful reductions in anxiety.

- A form of acupuncture that stimulates the vagus nerve has also been used to successfully reduce anxiety before surgery. Yes, this isn’t nVNS, but it uses the same mechanism.

The pattern is consistent: when the nervous system shifts from a sympathetic, fight-or-flight state, anxiety eases.

Unlike some of the other things you may have tried, ear-based vagus nerve stimulation is consistently accurate and convenient. You can yōjō while doing the cleaning up or commuting to work via train or bus, or while in a meeting. That makes it easy to do regularly.

Some of the things we try fail through inconsistency more than anything else.

What if nothing happens?

This sort of caution is perfectly normal. Uncertainty about something like vagus nerve stimulation raises the perceived risk.

The truth is VNS doesn’t always create dramatic changes right away.

It works through regulation over time — improving balance, recovery, and stress tolerance.

This is why yōjō created a nervous system care platform.

We know vagus nerve stimulation works best when it’s done daily. Irregular use makes it much harder for the nervous system to adapt.

And we’ve seen changes in our members’ heart rate variability, stress index, and parasympathetic activity scores. Better sleep and mood are two of the first things members notice a few weeks after starting with yōjō.

Changes are gradual. Consistency is key.

There’s no reason vagus nerve stimulation can’t work for you — especially when it’s used consistently and with guidance.

What if it changes or numbs me?

Vagus nerve stimulation does not work like medication. It doesn’t blunt or override your nervous system. Instead, it supports vagal activity, which naturally reduces excessive threat signalling.

Your body and your mind relax because there’re no immediate dangers. Your personality and emotional range have nothing to do with it.

Studies show that vagus nerve stimulation:

- Reduces activity in the amygdala, the brain’s fear center

- Lowers activity in the hippocampus, involved in emotional memory

- Increases activity of GABA, a calming brain chemical that reduces overstimulation

I don’t want to do it wrong

Without guidance, even simple tools can feel overwhelming.

When should I use this? How often? How do I know it’s helping?

Unlike some cervical VNS options (devices that target the vagus nerve through your neck), ear-based vagus nerve stimulation for anxiety has simplicity on its side.

The earpiece fits snugly and stimulates the branches of the vagus nerve that sit very close to the surface of your ear. Either ear is fine.

A yōjō session lasts 30 minutes, and you can adjust the intensity.

Relax Mode for relaxation, Stress Mode for resilience, Energy Mode for vitality, and Sleep Mode for, well, sleep. Each mode is carefully engineered to provide the appropriate stimulation.

The only way you can go wrong, really, is by NOT using your yōjō vagus nerve stimulator at least once a day.

So a VNS stimulator will work for my anxiety?

Yes. The evidence shows that vagus nerve stimulation can reduce anxiety by:

- calming overactive fear circuits in the brain

- increasing neurotransmitters that calm signalling in the brain

- shifting the body out of chronic fight-or-flight and into rest-and-digest

- supporting a physiological state of safety

A good stimulator works by calming your body’s stress response and changing how certain parts of your brain behave. Changes take time, so you may want more than just a device. A support system that helps you stick to vagus nerve stimulation like a ritual you can’t live without, perhaps?

Showing

items out of

Filtering by:

.png)

Article

January 30, 2026

time

-min

read

What Is Vagal Tone?

Learn what vagal tone is, how it works, how it’s measured, and why it matters for stress resilience, emotional regulation, and long-term health.

Vagal tone describes how responsive the vagus nerve is, particularly in regulating heart rate and stress responses, and how effectively the nervous system can return to balance after activation.

In simple terms, vagal tone reflects how easily your body can calm itself after stress.

The vagus nerve is the main nerve of the parasympathetic nervous system — the branch responsible for rest, digestion, recovery, and repair. Vagal tone reflects how strongly, and how flexibly, this system can influence the body to maintain internal balance, also known as homeostasis.

At a physiological level, vagal tone affects heart rate, breathing, digestion, inflammation, and emotional regulation. When vagal tone is high, the body can respond to stress and return to baseline efficiently. When it’s low, the nervous system is more likely to remain in a heightened state of activation.

The vagus nerve acts as a two-way communication pathway between the brain and the body, continuously carrying information about internal conditions and environmental demands. Vagal tone tells us how well that communication supports regulation.

In research and clinical settings, vagal tone is most often discussed in relation to stress resilience, emotional regulation, and cardiovascular health.

Why ‘tone’?

In physiology, ‘tone’ refers to baseline activity.

Muscle tone, for example, describes a muscle’s constant, low-level readiness to contract and relax. A muscle with healthy tone is responsive, not tense or rigid.

Vagal tone follows the same principle. It describes the ongoing influence of the vagus nerve at rest, and how easily that influence can increase or decrease as conditions change.

High vagal tone doesn’t mean the vagus nerve is constantly active. It means the nervous system has a strong capacity for regulation — the ability to slow things down when needed, and to release that influence when action is required.

How vagal tone works

One of the most important features of vagal tone is known as the vagal brake.

The vagus nerve contains fast, myelinated fibres that connect directly to the heart’s pacemaker (the sinoatrial node). These fibres act as a brake on heart rate.

When vagal influence is high, the brake is applied, slowing the heart and supporting calm, restorative states. When reduced, the brake is released, allowing heart rate to rise and support attention, movement, or mobilization.

This braking and releasing happens continuously. A well-functioning vagal brake allows the body to respond to changing demands without becoming stuck in a prolonged stress response.

How vagal tone is measured

Vagal tone isn’t measured directly. Instead, it’s inferred from patterns in heart rate — most commonly through respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA).

RSA refers to the breath-by-breath changes in heart rate that occur naturally as you breathe. Heart rate increases slightly during inhalation and slows during exhalation.

The size of this breath-linked change in heart rate reflects how strongly the vagus nerve is influencing the heart.

- Higher RSA is associated with stronger cardiac vagal tone

- Lower RSA suggests reduced vagal regulation

RSA is widely used in research as a marker of autonomic flexibility: the nervous system’s ability to adapt to stress and return to baseline.

Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) and vagal tone

Vagal tone is shaped by repeated signals to the nervous system, particularly signals that support parasympathetic activity and recovery.

Both invasive and non-invasive forms of VNS influence vagal activity, often reflected as increases in heart rate variability and improvements in autonomic balance. By directly stimulating vagal pathways, VNS can engage the same regulatory circuits involved in slowing heart rate, reducing inflammation, and supporting recovery.

Far from forcing relaxation, regular VNS changes how efficiently the nervous system can apply and release vagal influence over time, which is a core feature of healthy vagal tone.

Why vagal tone matters

Vagal tone is widely considered a physiological marker of stress vulnerability and resilience.

Lower vagal tone is associated with poorer emotional regulation, chronic low-grade inflammation, cardiovascular disease, depression, and stress-related disorders.

Higher vagal tone supports emotional stability, physiological calm, and the processes involved in growth, restoration, and repair.

.png)

Article

January 23, 2026

time

-min

read

What Is the Vagus Nerve, and What Does It Do?

Here’s a simple look at something gaining attention in wellness, and why it can change how your body responds to stress.

If you’re wellness aware, you’ve probably heard of the vagus nerve. And, if you’re smart enough to be skeptical of praises and promises in the wellness space, you’re probably looking to know more about the “body’s calm switch” and why this one nerve can do so much.

What is it? Where is it in the body? What information does it carry? How does it help the body to regulate?

Simple answers to these questions will help you better understand the vagus nerve’s influence on stress, digestion, inflammation, mood, and social connection. It will become clear why this particular nerve is becoming more prominent for well-being and why vagus nerve-based therapies and interventions often produce broad effects, rather than isolated symptom changes.

Let’s take a quick wander around what has been called “The Wanderer”.

The vagus nerve and its connections

The vagus nerve — 10th cranial nerve — is the longest of the cranial nerves and the primary component of the parasympathetic nervous system. Its name comes from the Latin vagus, meaning “wandering,” reflecting its path from the brainstem through the neck, chest, and abdomen, connecting your brain to your heart, lungs, gut, liver, spleen, and kidneys.

It was first described in the second century by Galen of Pergamon, a prominent Roman physician. He recognized the vagus nerve’s importance for vitality and linked it to life force.

Despite being talked about as a single nerve, the vagus nerve is actually a pair of nerves running down the sides of your body. And despite being spoken of as a motor nerve, the vagus nerve is mostly sensory.

Roughly 80% of its nerve fibres are afferent, carrying sensory information from the body to the brain. The other 20% send signals from the brain to the organs.

This makes the vagus nerve less of a command system and more of an information superhighway coordinating multiple systems to help maintain homeostasis — the body’s internal balance, especially when it comes to stress, recovery, digestion, and feeling safe.

It is involved in heart rate, blood pressure, breathing, digestion, immunity, mood, speech, and even taste.

In practical terms, the vagus nerve helps your body do three key things:

Calm down after stress

The vagus nerve is a core part of the parasympathetic “rest-and-digest” system. It counterbalances the fight-or-flight response and helps bring the body back into balance once a challenge has passed.

One of its roles is acting as a “vagal brake” on the heart, gently slowing the heart rate and supporting a state of calm, flexible alertness rather than constant tension.

It’s also a major pathway in the microbiome–brain–gut axis, enabling gut activity and microbial signals to influence mood, cognition, and emotional regulation.

This helps explain why chronic stress often shows up as digestive issues — and why improving nervous system regulation can change how the body responds to stress overall.

Manage inflammation

The vagus nerve helps keep inflammation in check.

Through a built-in inflammatory reflex, it can signal the immune system to reduce excessive inflammatory responses, helping protect the body from chronic, stress-related inflammation.

When inflammation rises in the body, afferent vagal fibers signal the brain. In response, efferent vagal pathways help dial down excessive immune activity through a mechanism called the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway — CAP for short.

CAP is a loop involving the vagus nerve and acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter.

- Your body detects inflammation and lets your brain know by sending signals up the vagus nerve.

- The brain sends a signal back down the vagus nerve, calling for the release of acetylcholine.

- Acetylcholine, once released, finds immune cells called macrophages and attaches to specific receptors on the cells.

- The cells stop releasing inflammatory chemicals.

It may seem like immune suppression, but this regulatory process is essential for long-term resilience because it prevents overreactive immune responses.

Feel safe

The polyvagal theory suggests that for mammals, being social is a biological necessity for regulating our bodies and surviving. We use social cues (like a soothing voice or a smile) to tell each other's nervous systems that we are safe, which turns off the defensive, inflammatory systems. And the vagus nerve is central to this sociality.

Through its connections with muscles of the face, throat, and ears, the vagus nerve helps regulate facial expression, vocal tone, listening, and speech.

This, according to the theory, is why a sense of calm, and its opposite, can spread around a room.

Balance is key

The vagus nerve isn’t really a switch you flip. That has been a handy analogy, but it doesn’t explain how complex and nuanced the vagus nerve’s work is.

It’s more like a learning pathway, continuously updating the brain about internal states and shaping how the body responds to stress, connection, recovery, and challenge.

Lasting calm emerges when regulatory systems are trained, consistently and gently, to identify threats, recognize safety, and adapt quickly but never too much of one and not enough of the others. Homeostasis is the final and most vital goal.

And that’s why working with the vagus nerve tends to change more than one thing at a time.

.png)

Article

January 16, 2026

time

-min

read

Most of You Is Automated

Here’s how the autonomic nervous system keeps your body in balance, and what happens when stress takes over.

Your body is running a thousand background processes right now — pumping blood, digesting food, healing microscopic damage, and adjusting hormones — all without you thinking about it.

That’s the autonomic nervous system (ANS) at work: the silent regulator connecting your brain and spinal cord to every organ, tissue, and cell.

It keeps you alive — and in balance — without ever asking for your attention.

What is the ANS?

The ANS is your body’s autopilot.

It maintains vital functions like heart rate, breathing, digestion, and immune response — automatically and continuously.

It’s made up of three main branches:

- Sympathetic nervous system – your body’s stress responder (fight-or-flight).

- Parasympathetic nervous system – your recovery and repair mode (rest-and-digest).

- Enteric nervous system – your gut’s independent control center.

The enteric system manages digestion. The other two are constantly balancing each other — one energizing, the other calming — to maintain homeostasis, your internal equilibrium.

The sympathetic nervous system

When things get intense, this system takes charge.

The sympathetic nervous system prepares you for action. It’s the one that saves you from danger, sharpens focus, and floods your body with energy.

Once activated, it:

- Releases adrenaline and other stress hormones.

- Raises heart rate and blood pressure.

- Shifts blood flow to your muscles and brain.

- Reduces blood flow to the gut and skin.

This is the fight-or-flight response: essential for survival, but harmful when it stays switched on too long.

Chronic activation can lead to high blood pressure, inflammation, poor digestion, and fatigue.

The parasympathetic nervous system

Once the danger has passed, the parasympathetic system steps in.

This is the body’s rest-and-digest network: it slows things down so you can repair and replenish.

When active, it:

- Slows heart rate and lowers blood pressure.

- Increases digestion and nutrient absorption.

- Dilates blood vessels, improving circulation to vital organs.

- Balances inflammation, promoting healing.

The star player here is the vagus nerve — the longest cranial nerve in your body. About 75% of its fibers are parasympathetic, connecting your brain to your heart, lungs, and gut. Through this nerve, the parasympathetic system influences everything from mood and immunity to metabolism and sleep.

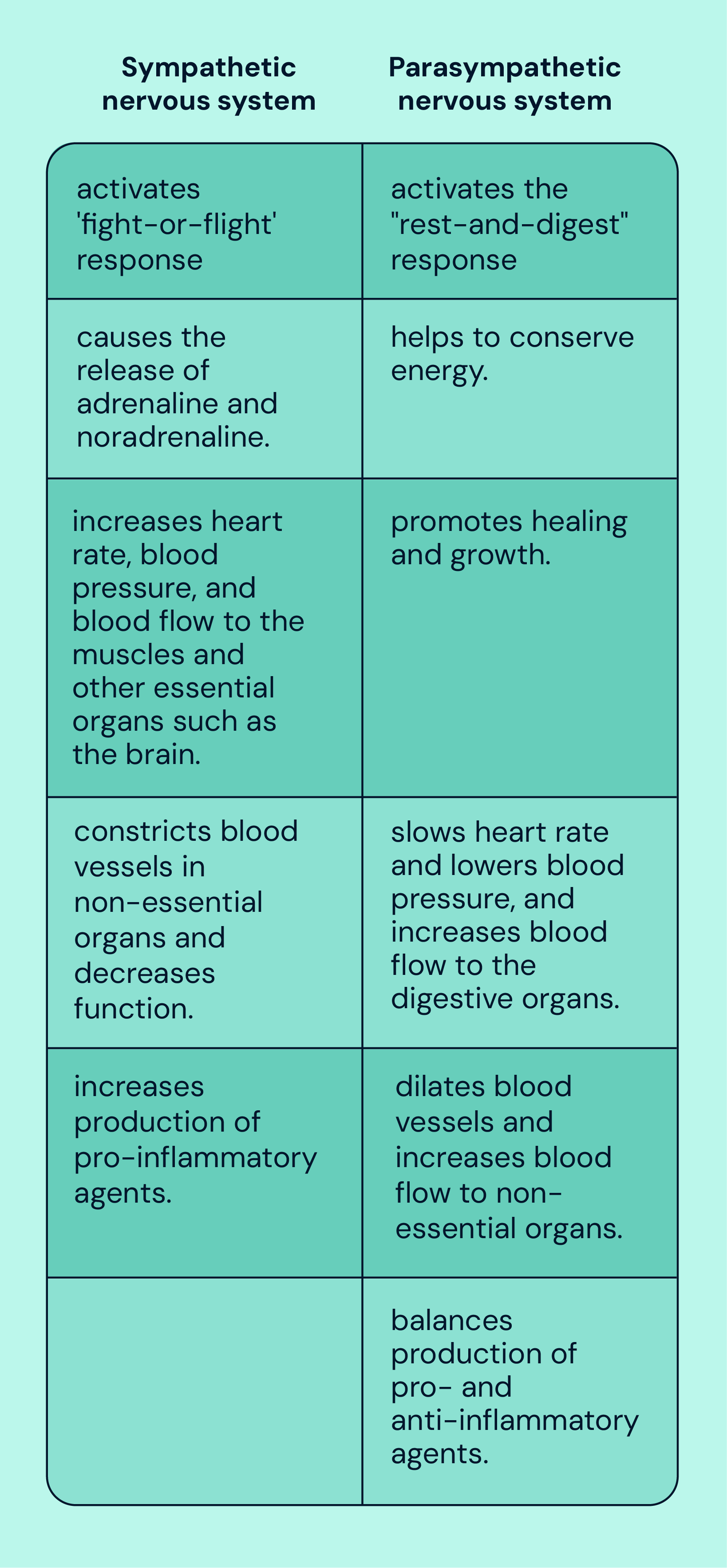

Sympathetic vs. parasympathetic

Here’s how these two systems work together — and why that balance matters:

When the stress response dominates, as it often does in modern life, your sleep, digestion, and mental clarity begin to suffer.

Why it matters

A well-balanced autonomic nervous system is essential for resilience — your ability to recover from stress and maintain health.

When the fight-or-flight response and the rest-and-digest response work in harmony, your body adapts efficiently to challenges and then returns to calm.

But when stress wins out, inflammation rises and chronic imbalance sets in; the physiological foundation for burnout, anxiety, poor sleep, and chronic disease.

The takeaway

A lot of what keeps you alive happens automatically. But that doesn’t mean you’re powerless to influence it.

Through tools like breathwork, movement, biofeedback, and vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), you can help your nervous system rediscover equilibrium, the state your body was designed to live in.

Article

January 9, 2026

time

-min

read

Five Easy Ways to Support Your Vagus Nerve

Your vagus nerve plays an important role in helping your body manage stress, digestion, and recovery. Here are five simple, everyday ways to support it.

The vagus nerve is a key part of the body’s system for calm and regulation. It helps influence heart rate, digestion, immune responses, and how the body adapts to stress. Vagal activity is associated with resilience and recovery.

In today’s fast-paced world, ongoing stress can place extra demand on the nervous system. When the body struggles to shift out of a constant “on” state, this may contribute to challenges such as poor stress regulation, inflammation, or digestive discomfort.

There are clinically studied ways to stimulate the vagus nerve, including non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation (nVNS). Alongside these, there are also simple, natural practices that may help support vagal activity as part of everyday life.

Embrace the cold

Brief cold exposure can encourage activation of the parasympathetic nervous system. This might include a short cold shower, a dip in cool water, or even splashing cold water on your face. These experiences can prompt the body to shift toward a calmer, rest-and-digest state.

Breathe mindfully

Breathing is one of the few automatic bodily processes you can consciously influence. Slow, deep breathing that engages the diaphragm can help signal the body to relax, supporting heart rate regulation and parasympathetic activity.

Try this

Place one hand on your chest and the other on your stomach.

As you breathe in through your nose, allow your belly to rise while keeping your chest relatively still.

Exhale slowly through your mouth.

This style of diaphragmatic breathing can help support vagal function and encourage a calmer physiological state.

Sing, hum, chant … or gargle

The vagus nerve has branches that connect with the muscles of the throat and vocal cords. Activities such as singing, humming, chanting, or even gargling can create gentle vibrations in this area, which may help stimulate vagal pathways.

Get moving

Physical activity supports the nervous system as well as the muscles. During exercise, the body becomes more alert, while recovery afterward relies on parasympathetic activity to restore balance. Over time, this process can help train the nervous system to move more efficiently between states of activity and rest.

Regular movement is associated with better stress recovery and overall nervous system health.

Socialize and laugh

Social connection plays a meaningful role in nervous system regulation. Spending time with others, sharing positive experiences, and laughing can support parasympathetic activity and are linked to lower stress levels and improved heart rate variability.

Supporting your vagus nerve doesn’t require dramatic lifestyle changes. Small, consistent practices can help create the conditions for better balance and resilience over time.

For those seeking a more targeted approach, non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation (nVNS) is a clinically studied option designed to stimulate the vagus nerve safely and effectively.

.webp)

Article

December 11, 2025

time

-min

read

What Everyone Gets Wrong About Burnout

Burnout isn’t a character flaw. It’s biological. Here’s what’s really happening beneath the surface, and how to restore balance.

Burnout is a state of emotional, physical, and cognitive exhaustion caused by prolonged stress. It’s marked by depleted energy, reduced motivation, and a sense of detachment from work or life.

Most conversations about burnout circle the same three ideas:

- You’re no longer aligned with your work.

- The cult of productivity won’t let you rest.

- Your mindset needs a reset.

All true — but they miss the real point.

Burnout feels philosophical, even spiritual, but at its core, it’s biological. Down-and-dirty, animal biology. It’s what happens when your body’s survival systems forget how to stand down.

Your stress response was built for short bursts of action. A chase. A threat. A deadline. When those bursts never end, the stress never stops — and your body forgets how to switch off, and it’s “all systems go” all the time.

At first, it’s just overdrive. Then, it becomes dysfunctional.

Cortisol floods your system. Your immune response activates. Low-grade inflammation spreads quietly through your tissues. Your brain reads this chemical chatter as a sign of danger. Even when you’re sitting still, your body’s braced for attack.

That’s burnout: a body in fight-or-flight, running on fumes, trying to save energy for life-saving tasks that never come. Your mood drops, your focus fades, you start conserving — not because you’re weak, but because your body thinks it’s protecting you.

And because the stress keeps coming, the inflammation keeps burning. The stress-inflammation-stress cycle loops and loops.

The good news? Low-grade inflammation is manageable — even reversible — when the nervous system is taught how to regulate again.

That’s what yōjō helps people do.

We use science-backed tools — vagus nerve stimulation, biofeedback, and personal coaching — to restore balance to your nervous system and help it remember how to rest, recover, and reset.

Article

November 4, 2025

time

-min

read

Itutu: A Philosophy of Calm

Mastering this mindset helps you tackle life’s little stresses before they snowball.

Chronic stress fuels inflammation. Inflammation fuels disease. And before you know it, you're caught in a cycle that wears down your body, ages you faster, and drains your energy. In short, stress is your enemy. The best way to deal with an enemy is to choose only those battles you can win.

There are the big stresses in life and the small stresses. We hardly need to explore the big stresses; we all know them. There’s no winning against them. They just are, and we do our best to accept them. The small stresses, however, we can conquer the minute they kick up a fuss.

These are the less remarkable, less noticeable stresses. Those dozen or so situations and happenings that tense up your mind just a smidge, like a person tightening a guitar string. Just a little at a time. The tardy bus, the broken shoelace, the spilled coffee, the rude coworker, the winding queue, the stolen seat, all piling on top of each other, turning that mind string until it is so tense your entire being develops a distinct, steely twang.

There may be many, and they may sometimes be hard to see, but one West African approach to life can help you thwart these little enemies and stop them from strumming your nerves with their fingers.

It’s called “itutu.” It is a way of seeing minor stresses and worries that takes the sting out of them.

As The School of Life explains in their video, A Philosophy of Calm, itutu “denotes a particular approach to life: unhurried, composed, assured, and unflappable.” Among the Yoruba people, to “have itutu” is to embody coolness — to meet frustration with poise and to remain untouched by the noise of small misfortunes.

This calm isn’t a divine gift; it can be learned. It’s the fruit of knowing, as the Yoruba say, that some things belong to “àṣẹ” — the natural order — and lie beyond our control.

Anger arises when we overestimate our power to change external reality. Itutu arises when we see the limits clearly and choose peace within them.

Modern science would call this emotional regulation, the ability of the prefrontal cortex to modulate limbic reactivity. When you practice the qualities embodied by itutu, you train your nervous system to stay out of fight-or-flight.

Over time, this translates into measurable benefits: lower cortisol, steadier heart rate variability, reduced inflammation, and potentially improved longevity.

Cultivating this mindset makes you resilient. You learn to save your energy for what truly matters, and your calm becomes your default setting.

Oops, no results found

We couldn’t find any insights that match your current filters.

M.D., Ph.D., FASRA

Chief Medical Officer

Professor Emeritus of Anesthesiology, Orthopaedics, and Pain Medicine at the University of Florida College of Medicine, Boezaart has 35+ years of clinical expertise and champions evidence-based, person-focused strategies to improve quality of life.

.webp)